As I reflect on another splendid year presenting/teaching engineering methods and helping Accuris customers find the right tools and support to creatively design the products of the future, I conclude that one phrase sums up a recurring theme for 2024: “working through uncertainty.”

I realised long ago that if I don’t learn something when I present then I haven’t sufficiently extended either my or my audience’s comfort zone and the members of the audience haven’t learned as much as they could have. Therefore, I probably won’t have been as useful to them as I could have been.

For example, in one of my sessions at the 2024 Aircraft, Airworthiness & Sustainment Conference in San Antonio, Texas, I explored all three aspects of designing and assembling deceptively simple bolted joints.

I’ve explained on numerous occasions the uncertainties and sometimes dubious assumptions in classic textbook theory used to specify how much pre-tension force should load the joint – especially when the joined components are made of different materials, and a range of operating temperatures are involved. Good design practice results in a range of pre-tension which, to minimise fatigue stresses, will be as high as possible without risking bolt yield. This is as much as most university courses have the time and awareness of industrially relevant methods to teach.

Beyond that, there is more uncertainty in how accurately the bolt is tightened (to a value within that range) during assembly. Most companies use a standard “torque wrench” and calculate the setting using a classic textbook formula. Unfortunately, even under factory assembly conditions, the accuracy of attaining the desired preload can vary by plus or minus 25%.

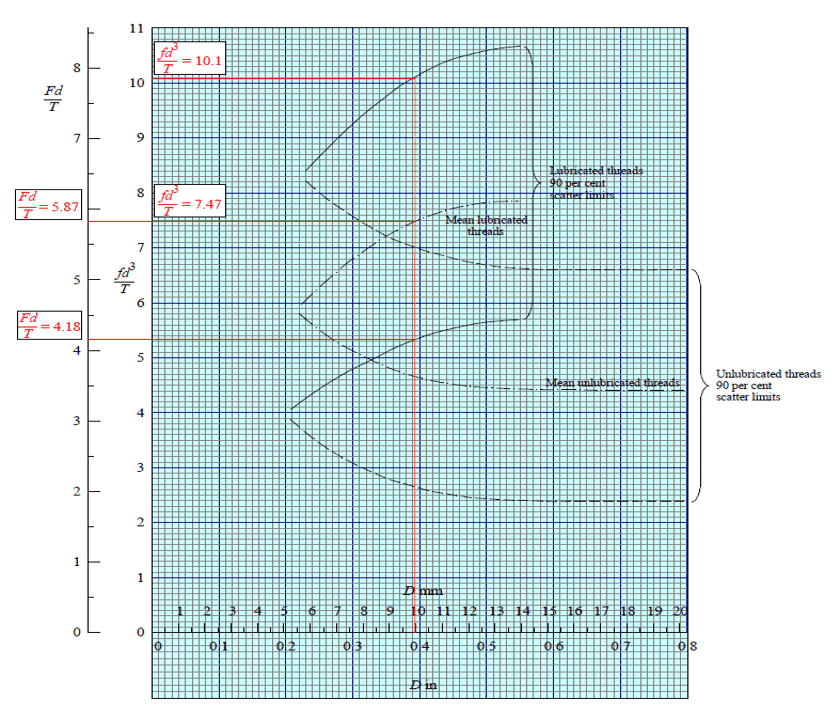

Related to that, it is impossible to produce an empirical relationship that gives a precise solution to the problem of measuring the applied torque. Thankfully, an analysis of the extensive test results available within the ESDU methodologies provides a method of determining, for small nuts and bolts, approximate values of tension induced by a specific torque.

Graph showing scatter bands representing uncertainty

The third aspect of the challenge of practical bolted joints is their potential for self-loosening. While an adequately tightened nut-and-bolt assembly is not likely to loosen in service under steady operating conditions, up to 20% of pre-load might be lost when the surfaces of the mating components bed-in. Other and more serious losses of clamping force can occur when bolted assemblies are subjected to (often unexpected) vibration in service.

In presenting a typical example of self-loosening experienced by one of ESDU’s European customers and its solution with our validated methods, it was rewarding that two engineers came to me after my talk to discuss the very same problem that they were trying to solve on one of the aircraft types in their fleet.

The interesting part of the story was that these engineers and our European client did not know with any certainty why their bolts occasionally self-loosened – but our client’s modified joint hasn’t subsequently had that problem!

Lastly, my presentation was to engineers who are rightly required to use validated methods, data and software that will meet the stringent requirements of aircraft certification. Back in the UK, I was discussing another bolted joint with an engineer working in a “general engineering” application, where the product’s assembly instructions noted “WARNING: Do not overtighten.”

In addition to the vague instruction, there was also no account taken of temperature, whether the nuts and bolts were to be lubricated during assembly plus a cheap bolt with a coarse pitch thread form was chosen. The engineer did acknowledge that “there were sometimes problems in cold weather”…

While bolt failure in general engineering may not result in the catastrophic consequences that could occur if an aircraft joint fails or “comes loose,” the damage to any business’s reputation and bank balance from not addressing such a solvable problem during design can still be very serious. It is both professionally and personally rewarding that ESDU’s validated methods, supported by our engineering service, provide practical solutions to all aspects of bolted joint design and in-service operation for those seeking better and safer products.

Happily, if there’s one thing certain in 2025, it’s the ongoing pleasure that my Accuris colleagues and I will get from helping other engineers be aware of – and deal with – uncertainties in their professional work!

Want to hear more of John’s perspectives on engineering in the aerospace & defense sector? Watch the recording of our webinar where he chatted with Rolls Royce engineer Chris Burrows.